During these uncertain times, SMoCA has invited artists and staff to utilize our blog Inspire as an outlet to make meaningful connections by sharing personal reflections and insight into their practice.

This week, plastics historian and writer/journalist Christopher Geoffrey McPherson lends his expertise to detail a brief history of melamine, a mid-century plastic often used in tableware, and the future of sustainable plastics in everyday life.

History of Melamine

by Christopher Geoffrey McPherson

There was a time when plastics were hailed as a great new thing. They contributed to the prosperity that the United States (and other countries) enjoyed in the post-war 1940s and 1950s. In fact, one way or another, the plastics of the mid-century made life better for everyone, starting with their contributions to the war effort; for, the case can be made that—without plastics—the outcome of World War II might have been quite different.

More than a century after the invention of the first “modern” plastic (Bakelite in 1907), the attitude toward these miracle materials has changed—and rightly so. Now, plastics are viewed less as wonderful time-savers and valuable-resource substitutes, and more like the enemies of the natural world that they are.

Let’s put aside today’s modern attitudes and examine the great contributions made by another fantastic mid-century plastic: melamine. The melamine tableware that we know today can trace its beginnings to the needs of the United States Navy. Sometime around 1939 or 1940, the navy contracted with the Watertown Manufacturing Company (WMCo) to come up with a plastic replacement for ceramic dinnerware which it found to be too heavy, noisy, and fragile. By 1942, WMCo had created a working design that had been put into production and into use on ships. The melamine formulation they used was much harder, stronger and more stain resistant than other plastics that had been tried. By 1944, 90% of the company’s production was war related.

Melamine, for tableware, can trace a direct line to the success of using it for shirt buttons for the military. According to an American Cyanamid (AmCy) brochure: “[Melamine] plastic buttons were tried and found not only to be cheaper but more satisfactory because of their ability to stand up under long wear, rough usage and repeated laundering. … Naval craft were in need of sturdy, lightweight tableware. Here again [melamine] plastics, because of their hardness and resistance to boiling water, proved superior.”

According to a 1943 article in the Billings Gazette, the designer (Jon Hedu at WMCo) developed “streamlined plates [that] are resistant to boiling water, staining, knife cutting and will not crack. They weigh 80 percent less than crockery and conserve as much as 75 percent of storage space required.”

The tableware was tested for three years in the laboratory and in the field before being adopted for widespread use in 1942. (This field-testing might have included use on airlines; some information has appeared to suggest this. Aboard planes, three quarters of the weight and space required for paper plates is saved.) In short order, melamine had become the plastic of choice for the army, navy, and airlines.

Fast forward to the end of World War II, and WMCo made its “Watertown Ware” available to the public in August 1945. The response was tremendous, so the company asked its in-house designer, Hedu, to come up with another line specifically for consumers. “Lifetime Ware” was born. It was first used in tests in industrial settings starting sometime in 1946, and made available for purchase by consumers in 1947. “Lifetime Ware” was added to the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in 1947.

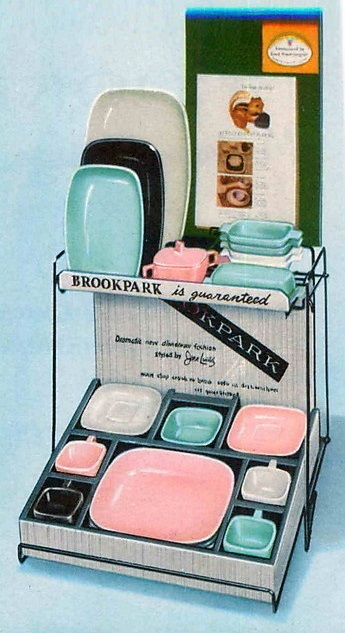

With the success of “Lifetime Ware,” WMCo discovered that it had another hit on its hands. In fact, they were receiving so many orders for this new tableware that the company had to institute three daily eight-hour shifts to try to keep up. According to an interview with Carl M. Siemon, past president of WMCo: “It grew [exponentially]. We had to make more molds and [introduce] more colors [just to keep up].” Soon, other companies jumped onto the melamine bandwagon. New lines introduced during this period included “Arrowhead” and “Boontonware” (also introduced in 1947), “Brookpark” and “Meladur” (1949), “Color Flyte” (1952), and “Residential” and “Florence” (1953).

The late 1940s and early 1950s can be said to have been the Golden Age for melamine tableware. Many designers became household names in part because of their work in melamine. In addition to Hedu, there was Joan Luntz (designer of “Arrowhead” and later of “Brookpark Modern”), Belle Kogan (“Boontonware”), Kaye LaMoyne (“Color Flyte”), Russel Wright (“Meladur”), and Irving Harper, of the George Nelson Associates design group (“Florence,” for Prolon).

In addition to the quickly spreading use of melamine, other plastics became common—like polyethylene (one of the plastics used in Tupperware) and polystyrene (most commonly used in picnic ware). This era also saw the rise of plastics in furnishings like vinyl, Formica, and others.

However, the plastic that was most familiar to most Americans was melamine; but consumer access to melamine tableware was, at first, restricted. In fact, Gimbels was one of the few department stores in New York City to sell melamine dinnerware, along with McCreery’s and Altman’s. Things changed when melamine tableware made its appearance in the 1948 Chicago Housewares show. Macy’s placed a large order and other department store chains across the country followed. Soon, melamine was being carried by some of the most famous department stores in America.

Even with the popularity of melamine for the consumer, some were not happy with these new tableware options. According to an interview with designer Joan Luntz, the companies that produced traditional china dinnerware put pressure on the department stores not to carry melamine at all. When that failed, they insisted that this new competition be kept separate, which led to the creation of “melamine centers” in many department stores. Keeping it separate made melamine look special, and consumers flocked to it.

As time went by, and competition grew even more fierce, traditional china companies took a different tack: they either bought existing melamine producers, or began to produce their own lines of melamine. This explains how early, heavy melamine came to be thinner, lighter and much cheaper in quality. The china companies were now able to say, with some accuracy, that plastic tableware was inferior to traditional china. This lowering in quality was the beginning of the end of melamine tableware as a household favorite.

By about 1960, most companies ceased producing the original, high-quality melamine. Many, like WMCo, sold their molds to other companies. In addition, the 1960s saw increased competition from foreign melamine makers flooding the market with cheaper-quality and less-expensive lines. The Golden Age of Melamine had ended.

Today, melamine is still used for many products—including dinnerware. Although the manufacturing of melamine causes some pollution, melamine dinnerware can last for decades, reducing the need to buy additional. (In fact, we use a set of “Lifetime Ware” as our daily dinnerware. It is now more than seventy-years old and still works wonderfully.)

Like other materials, one has to weigh the pros and cons of the use of plastics. Research is ongoing to create new plastics from materials that are more sustainable, that are less damaging to the environment, and easily biodegradable. These are all good changes and enrich the long history of plastics.

Additional information about mid-century plastics can be found at www.PlasticLiving.com.

Back to Inspire home.

CONNECTIONS: Spark | Amplify | Immerse