During these uncertain times, SMoCA has invited artists and staff to utilize our blog Inspire as an outlet to make meaningful connections by sharing personal reflections and insight into their practice.

This week, artist Claudia Bernardi writes about the significance of maps to her practice and how the idea of boundaries has changed during the current health crisis.

Cartography

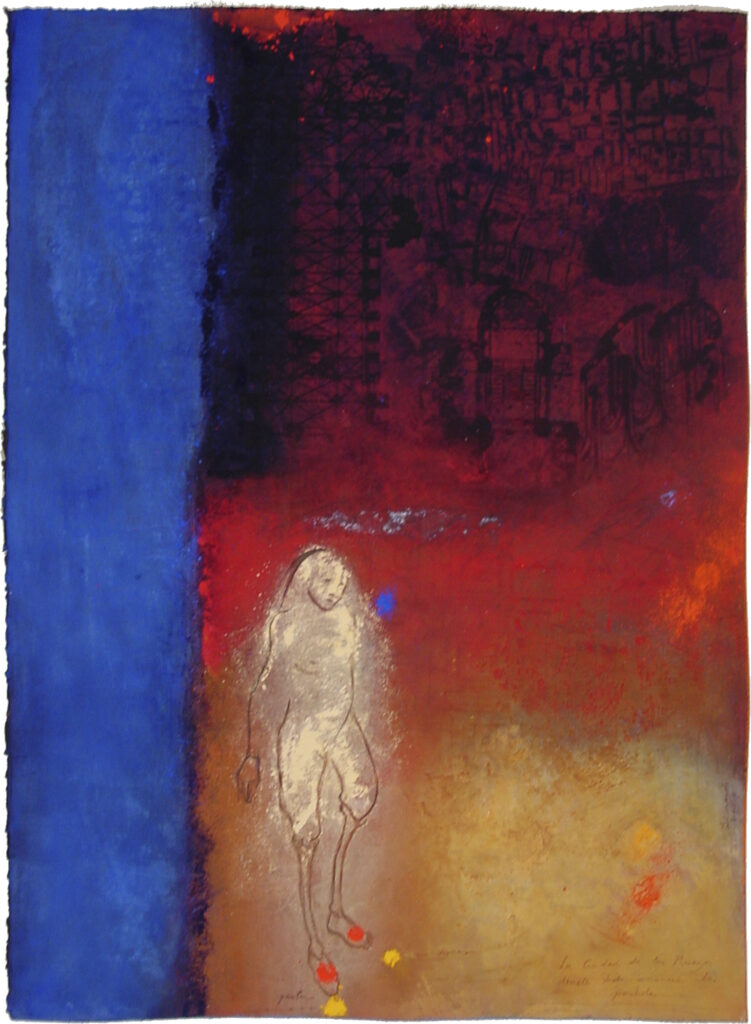

I love maps. I bury them underneath layers of powdered pigments of saturated colors. There are celestial maps and old maps of places discovered or imagined. The maps are infrequently seen clearly when the piece is completed. They remain discrete, unseeable unless paying attention. They are secret traces that function as inner structure of the fresco on paper. A story within a story, a way to simultaneously reveal and conceal an untold history.

Twenty years ago, I had the unique opportunity to study old maps of Latin America at the Bibliotheque Nationale de Paris. Wearing white gloves and being far enough from the old relic as not to run any risk of damaging such a treasure, I saw the southern coast of Brazil being delineated with segments of the coastline missing. The Andean mountain range was acknowledged timidly; rivers and lakes were absent; the length of the Amazon river was not comprehended. Distances were distorted. The territory that centuries later became my homeland, Argentina, was guessed correctly but it was incomplete as if the cartographer who had drawn that map had yet to return to the south of the continent to figure out what exactly was beyond the rocky surface that lied against the Atlantic Ocean. The renderings of the maps I saw were vague but the mass of land and water that it was depicted was still recognizable as our continent.

I am thinking of cartography during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The week of March 9–13, 2020, marked a limit, a frontier, a perdurable change, a dramatic reroute of lives, expectations, fears and preoccupations. It seems that prehistory is now comfortably resting in February and everything else that has happened since became this prolonged present of uncertainty that the world is cohabiting where time stretches flexible and disorienting. The social isolation recommended during the COVID-19 pandemic with its forced distancing among people and irrevocable seclusion appears to be the unique tool known to preserve health.

I live in a dramatic paradox: I know that the only reliable way to diminish the risk of getting coronavirus is to be isolated. Yet, I long to be with dear friends and family, with my students, and with my sister. I remember with nostalgia the last time I embraced a dear friend after a shared dinner. It was on March 13 at our favorite Chinese restaurant in Berkeley. Everyday gestures of affection have been marooned in an elastic past that swallows the present. Gatherings, concerts, going to work with fellow workers, exhibitions, lectures, classes, public transportation, in person teaching, and political rallies have become a memory of times past while we adapt and obey. I cannot imagine how or if the legendary march of human rights that has been taking place in Argentina every March 24 since the military junta ended as a relentless ritual of resistance towards the demand of justice, would ever happen again.

My plans, present and future, seem to have been pulverized. For the last 30 years I have been a community-based artist facilitating the creation of art projects, many of which took the form of collaborative murals, with survivors of massacres, survivors of political violence and forced exiles. I had the privilege to travel the world, from the north to the south of Latin America, Europe, and the United States. The maps of many countries were drawn with colors, shapes and lines that connected one collaborative mural with another one, a long, worldwide, persistent wall that captured personal and communal histories of people who had suffered the unimaginable but who still preserved the tenacity of living. These were the Walls of Hope.

My work as a community-based artist stood upon two main pillars: traveling and congregating. COVID-19 has decapitated this paradigm with the force of a malignant machete. Traveling is impossible or unsafe. Congregating may be a verb spoken in the past with little or no chance to be replicated in the future. Meeting large groups of people at once may be infeasible for a long time.

Last July, my sister and I were in Portugal. We learned that not far from Lisbon, one could visit Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point of continental Europe. On a beautiful and windy morning, we arrived at a small and humble location where there was not much besides a light house and a few unmarked buildings. And the sea. The vast, magnificent, and incomprehensible sea. The openness was so ample that it was hardly possible to relate to it as space, or distance, or water. It was frightening. Standing at the edge of the earth I wonder how I would draw the other side of the world, without knowing it, without understanding it. I firstly would have to trust that it was possible.

COVID-19, with its virulence and its capacity to harm, continues to draw a map of calamity and loss, of personal and collective catastrophes. All aspects of people’s life from health and economy to shelter, work, education, politics, safety, culture, resilience, death or surviving has been altered so profoundly that it is untraceable how will we be able to further adapt, for how long, and until when.

Suffering from uncertainty and anxiety and moved only by intuition, I find a tiny growth of a yet to be known Ariadne’s thread, a germinating pathway to discern and learn how to navigate this labyrinth designed by coronavirus. As a cartographer of this map of intention, I have to have faith that there will be another coast on the other side of this ocean of improvability. Most importantly, I ought to have confidence that I will do this with peers, with friends, and with companions, finding and sharing ways to overcome, and transform this demolishing solitude that coronavirus has imposed upon us in this year 2020.

We may have to conjugate the verb “to trust” as a form of militance and survival.

Claudia Bernardi

Staunton, May 2020

Claudia Bernardi

Professor, Community Arts

Diversity Studies

Critical Studies

California College of the Arts

Oakland and San Francisco, California, US

[email protected]

Founder/ Director

School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin

Morazán, El Salvador

Sincelejo, Colombia

[email protected]

www.wallsofhope.org

Artist in Residence

Spencer Center of Civil and Global Engagement

Mary Baldwin University

Staunton, Virginia

Back to Inspire home.

CONNECTIONS: Spark | Amplify | Immerse